Basics - Rhythm & trochees

Rhythm

The rhythm of spoken language is the basic framework of natural speech perception. It guides humans through their primary language acquisition process. It is the basis of phonological writing concepts (also known as ‘linguistic phonics’), and the basis of many spelling rules.

Objectives

The children are guided to perceive dynamic-musical elements (prosody/rhythm) in their speech by bringing these elements to the forefront of attention, and also naming them.

They are trained in the auditory perception of the stressed and unstressed parts of spoken sentences (intonation patterns), and especially the stress patterns of individual words (word stress).

The children discover that the syllable and, within the syllable, the vowel are the carriers of prosodic information, the rhythm.

The children consciously experience that speaking is a physiological event. In this module, the focus is on breathing.

Materials

Blackboard/whiteboard, blackboard magnets in two different sizes (or at least colours), chalk/pens.

Small round objects (counters) for laying out on the table/desk in two different, easily distinguishable sizes (buttons, tokens, small stones from the school grounds) collected in a box.

Exercise books, pens

Picture cards (from memory / domino games...)

Teaching approach/Implementation

Definition of terms

Breathing

Word stress

Emphasis – children’s names

Lexical terms

1) Definition of terms

The teacher recites a sentence and sets the outline so that the sentence explicitly has a very specific meaning.

e.g.: We’re going swimming today.

Then the sentence is spoken with a different emphasis.

e.g. We’re going swimming today.

We’re going swimming today.

The children have to explain the differences in the three sentences, and how they can tell what is meant.

What does the voice do? It gets louder/quieter, higher/lower, has more/less energy, you pause after the part that is important.

The terms

stressed (louder, higher, more energy) and

unstressed (quieter, lower, less energy)

pause

are worked out.

2) Breathing

Teacher asks: What is necessary for us to be able to speak at all, and sometimes with a lot of energy?

Possible answers from the children are enumerations of the organs of articulation or parts of speech, etc. However, we want to focus on the basis of speech, namely the airflow mechanism, Breathing.

The teacher explains to the children how many muscles have to work together so that our chest can expand and we can catch our breath and at what speed the air is then forced out again so that we can shout, cough and speak.

Exercise

Teacher: Take a deep breath and speak the text of a well-known song/poem until no sound comes out.

Reflection

Teacher: What happened? How did it feel? What did you discover/learn?

3a) Word stress/emphasis

The teacher has prepared the counters for laying out (e.g. small and large pebbles/shells/buttons...) in a box and asks child number 1: e.g. Matilda:

Teacher: If you have to "write"/lay your name out with counters - big ones for stressed parts, small ones for unstressed parts - how many counters would you need? How many big ones and how many small ones?

In all the exercises, the children should formulate their thoughts aloud so that we can follow their thinking towards the solution.

Teacher: How would you "write" your name now?

All the experiments should be read out loud.

This is especially important so that the children are motivated to interpret what they have written (and not as they think they have). We want to develop children’s auto-correction skills during the training, and part of this is that later on they will find it easier to recognize words they have misspelled if they read carefully.

All the children now lay their names out with counters (under the same conditions and with the same attention as child number 1).

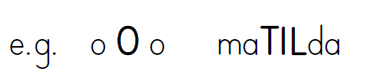

They write the names in their notebooks, first put the counters on top of them and then mark stressed and unstressed as small and large circles.

The children discover that exactly ONE large counter is always needed and learn that every word has ONE stressed part.

Rhythm exercises

Tapping/clapping stress patterns (two variations for stressed and unstressed!).

Speak all the children’s names which have the same pattern in a row - children take over the rhythm and speak in chorus

Children with the same patterns stand up/form groups

3b) Word stress - lexical terms

Picture cards are laid out, the pictures are named. The children place the corresponding stress patterns with the counters.

Then the words are written (chosen freely or decided by the teacher) in their notebooks and the symbols are drawn over them.

The children discover that the counters are always placed over certain letters: a, e, i, o, u.

They are asked to mark these places in the words with red.

Review

Conclude by getting the children to articulate what they have learnt in this lesson.

Trochees

‘Trochee’ is the name of the metrical foot which consists of two syllables and in which the first is stressed or “heavy”, and the second is unstressed or “light”. It is the predominant form of two-syllable words in German. It is frequent in English too, but less predominant because of the huge number of words of French and Latin origin.

In English, most trochaic words have as a “trademark” the weak vowel /ə/ (schwa) in the second syllable: this is mostly represented in writing by the letter <e>, sometimes in combination with <r> (but there are other spellings, including <a, or, our>, as in drama, squalor, colour). Many spelling rules can be explained by the trochee.

Objectives

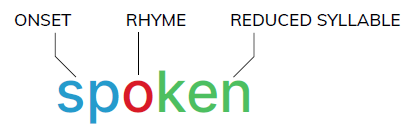

The children recognise the stress pattern of trochaic words: they perceive the heavy and light syllables and recognise the syllable boundary in the written word.

The children know that there are significant differences between the heavy and light syllables. The stressed first syllable is complex: it can have between zero and three consonant phonemes at the beginning (the onset); the vowel can be any of the 20 vowel phonemes of English EXCEPT schwa; and the syllable can be either closed (the vowel is short, and the syllable ends in a consonant phoneme) or open (the vowel is long, there is no closing consonant phoneme).

Materials

Blackboard or whiteboard

Chalk or marker (blue, red and green)

Foiled word cards (with magnets) for the board

Materials of/for students:

Hand mirrors for the children

Exercise books

Pens or pencils (blue, red and green)

Worksheets

Activities

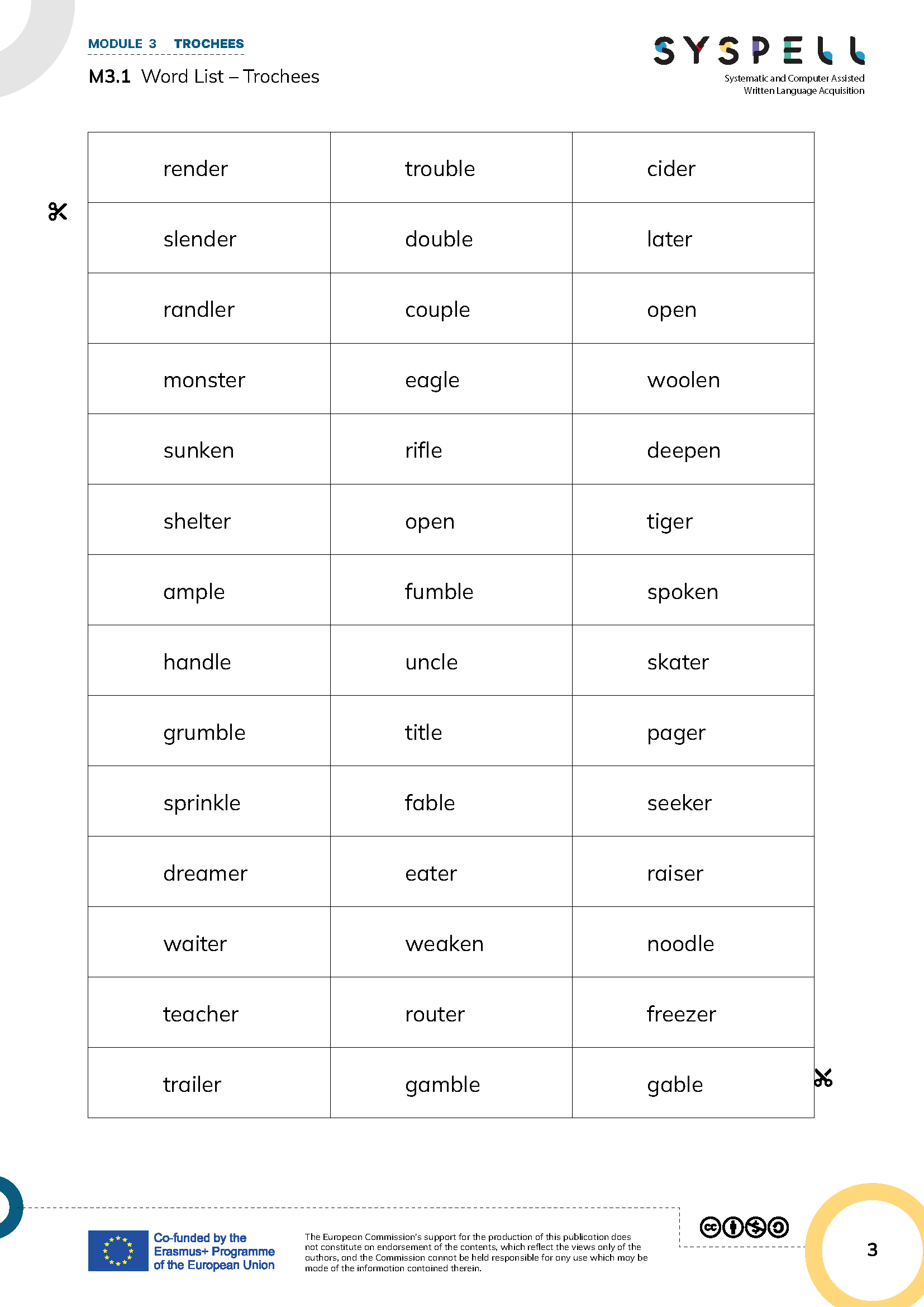

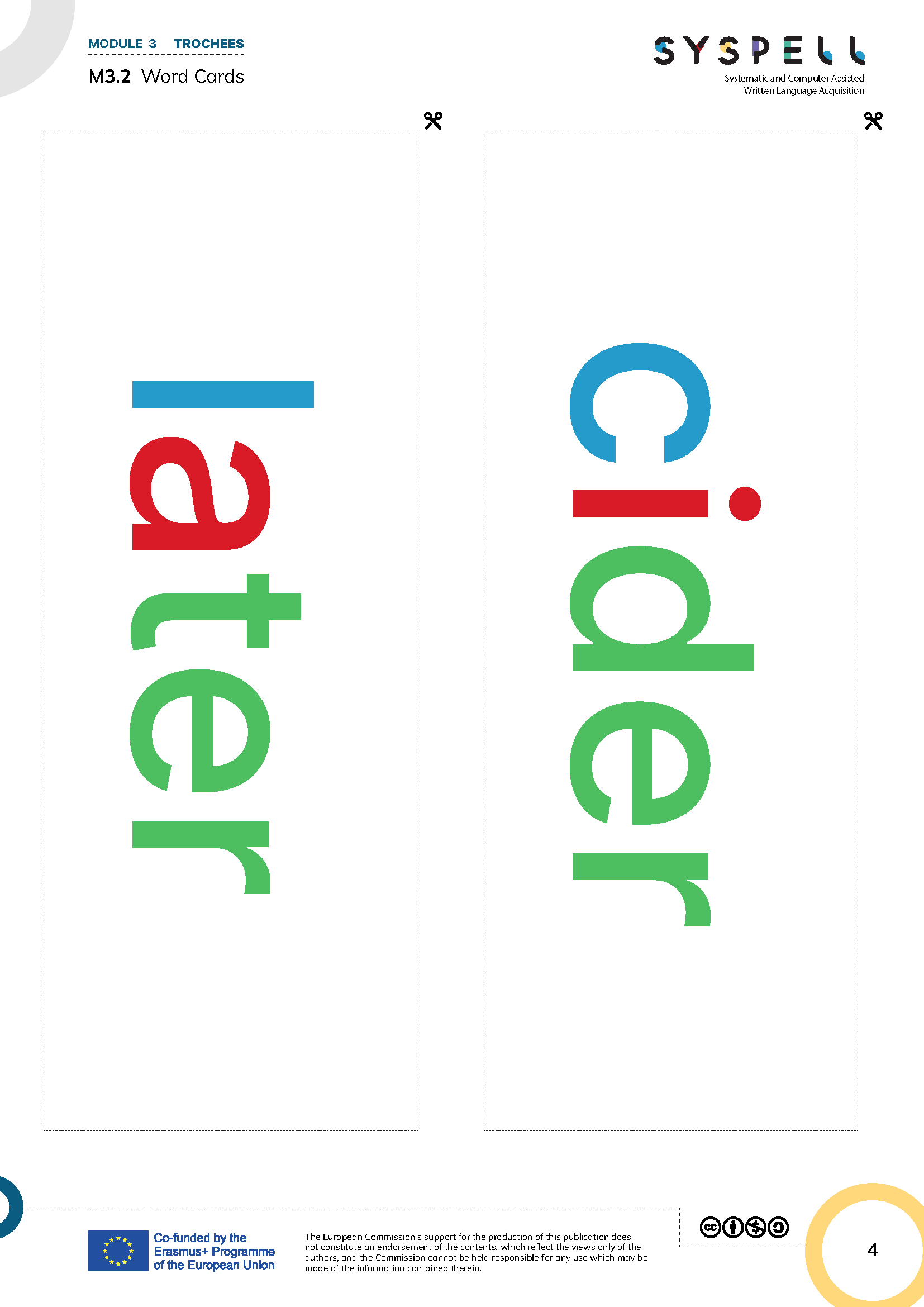

Introduction of Trochees M3.1 The teacher puts the word cards M3.2 the board in a random fashion, and asks the children to look carefully and say what they notice.

Possible statements from the children:

There are three colours.

They are all name words (nouns)

Some have several consonants at the beginning, some have none

All the words have a green syllable at the end

The teacher now directs the observations: “Let’s take a close look at the beginning of the words, what can we find out about them?” → Consonants, max 3, or even none → Children find their own examples.

Now let’s look at the red letters together. What are they called? → Vowels. Good! What else do you notice about all these words? → They all have a green part.

OK. Now look very carefully! There is something very special about the green syllables. Who can find it? → They all have the letter <e>! Great!

Now I have a task for you: Can you sort all the words on the board into three (3) categories? - Work and think together. Tell me your suggestions!

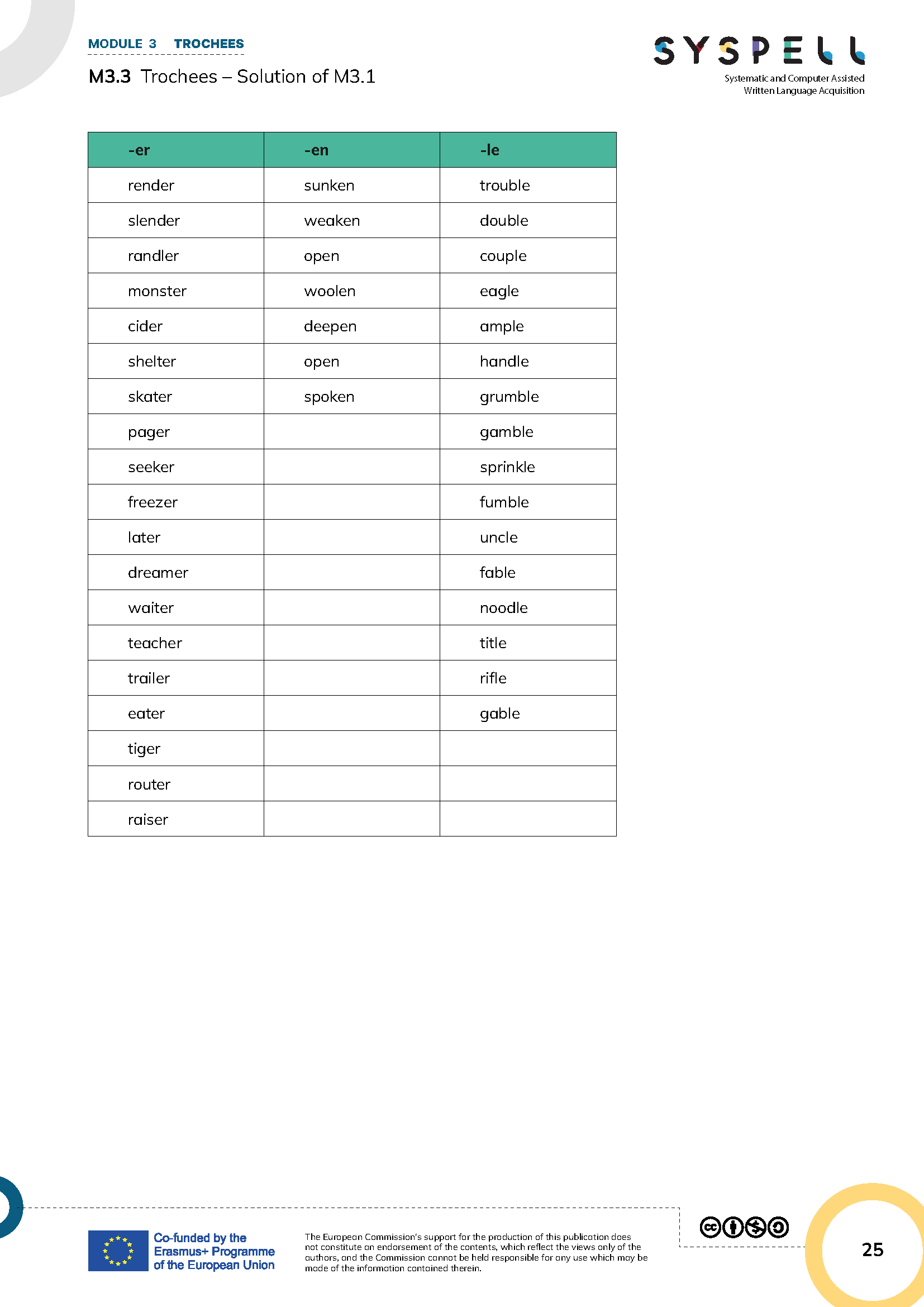

→ The intended solution is to sort them according to the type of unstressed/light syllable: el/le, en, er: see Table M3.3 TROCHEES - SOLUTION

Everything that comes from the children is discussed and valued. They are encouraged and motivated to find solutions until they (in the team) come up with them on their own.

Light syllable (reduced syllable). Now we’re going to concentrate on the light syllables, the ones written in green.

What does that mean? ‘Light syllable’?

Hint: Is it the opposite of ‘dark’? No – so what is its opposite? Yes – ‘heavy’. So what does it mean for a syllable to be ‘light’?

The light syllable is the quiet, unstressed part of the words on the board. When we read them, we notice that we hardly hear that syllable, or we may even swallow it altogether.

You see that all the words on the board consist of a stressed - important - we also say “heavy” part, and an unstressed “light” part.

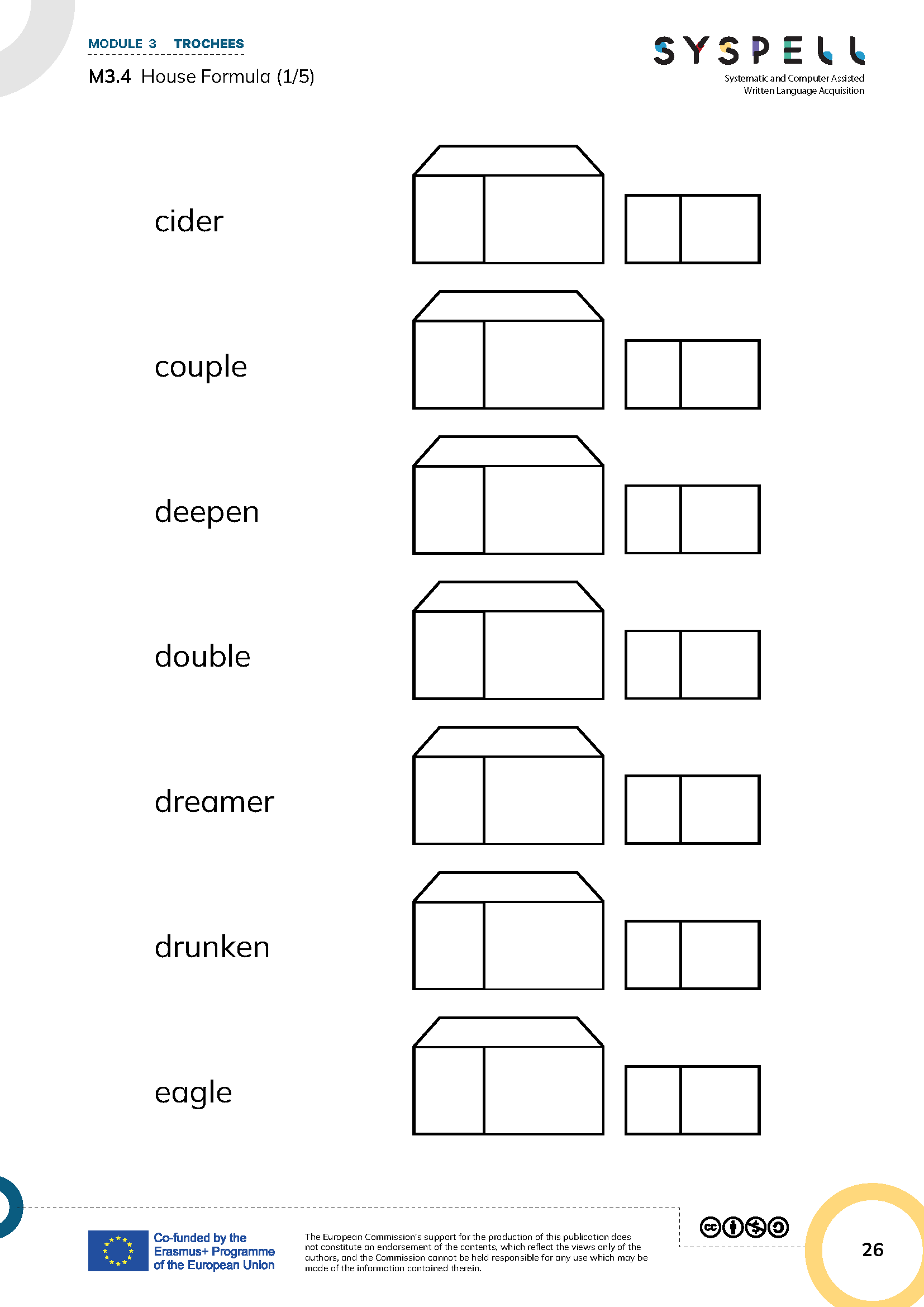

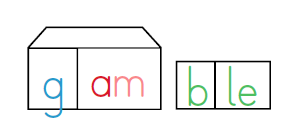

We can put words like this into a formula. Let me show you an example, using the word ‘gamble’:

We write the consonant letter <g> at the beginning in blue in the ‘front room’.

Next the vowel letter <a>, plus the consonant <m> which belongs to the first sylla- ble, go in the ‘living room’ – notice I’ve written the <a> in red and the <m> in blue.

Finally, the light syllable goes in the garage – the consonants <b> go in the motor- bike garage in green, and the green <le> (this has been an <el> and has changed in English into <le> over time).

Now let’s do the same thing with the word ‘gable’. Tell me where to put the letters, and what colour to write them in.

The aim is for the children to realise the heavy first syllable is open, = does not have a closing consonant – the letters <bl> again belong to the light second syllable.

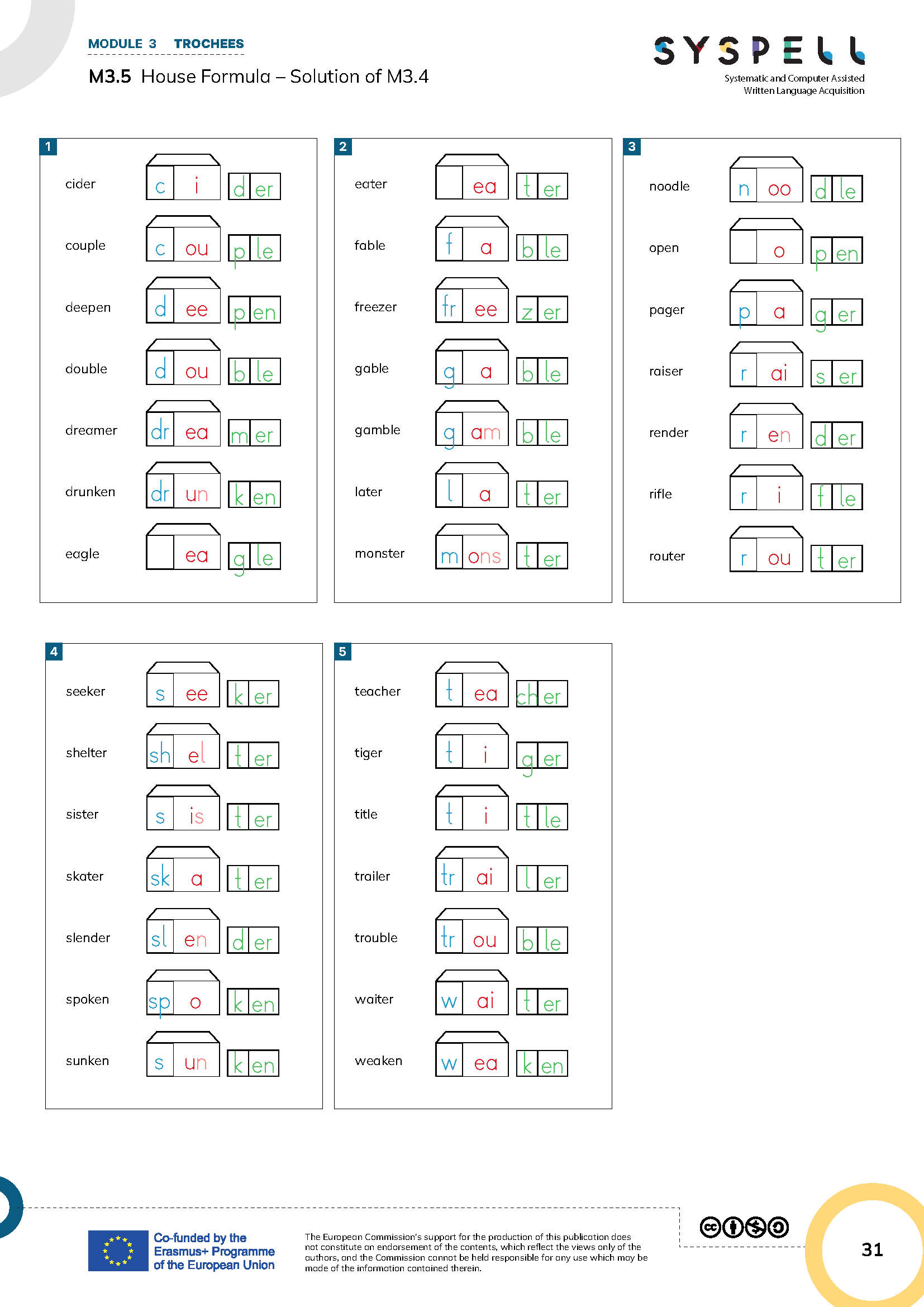

The teacher writes a few more words as examples on the board like shown in M3.5 HOUSE FORMULA SOLUTIONS .

Teacher: I’ve prepared worksheets for you to write the words on the board into, like I’ve shown you - M3.4 HOUSE FORMULAS

When they’re ready, the children’s attempts are requested, and shown on the board. Particular attention should be given to words with the same pattern as ‘gamble’:

Do the letters <m> and <b> belong to the same syllable, or should they be divided between them? Lead towards the answer: should be divided.

The teacher can use M3.5 HOUSE FORMULA SOLUTIONS to compare students results.

Exercise before next lesson

Find as many words as you can which have the same pattern as ‘gamble‘ or ‘table’ – One or more consonants at the start, a single vowel letter with a short sound, two consonant letters making different sounds, and ending in <le> and others like <er> ‘sister’, <en> ‘frozen’.